Crested Shelduck

Tadorna cristata

Anseriformes - Anatidae - Tadorna

The Crested Shelduck is a waterfowl species native to Northeast Asia. Initially, it was believed to be a hybrid of the Ruddy Shelduck and the Falcated Duck, but subsequent specimen studies have debunked this theory, establishing it as a distinct species1. Recent studies classify the Crested Shelduck as a unique evolutionary branch within the genus Tadorna, closely related to the Paradise Shelduck (T. variegata) and the Australian Shelduck (T. tadornoides)2. The Crested Shelduck is one of the most endangered waterfowl species, with no confirmed wild sightings for many years, making it highly likely to be extinct.

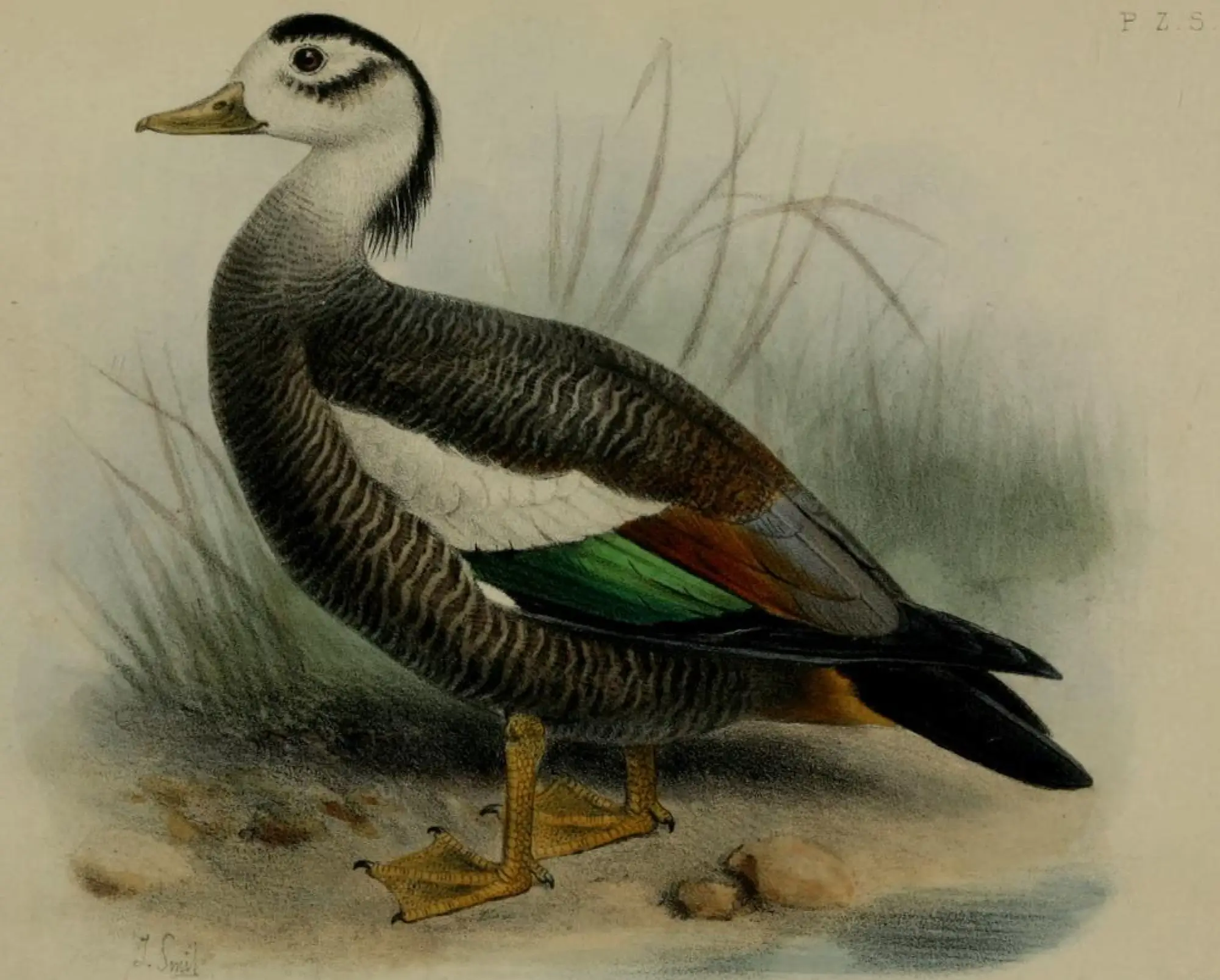

The Crested Shelduck is slightly larger than other similar wild shelducks. It is sexually dimorphic, with both sexes featuring prominent crests extending to the back of the neck, which gives the species its name. Males have a crest that is a deep, bronzed black-green color, a chest of a similar hue, a smoky gray head and neck, and a darker gray abdomen. Females have a black crest with two white eye rings near the ears, a white head and neck, and a slightly darker, brownish body compared to the males. Both sexes have white patches on their wings and pale red bills and legs.

Little is known about the habits of the Crested Shelduck. Based on sightings and speculation, their breeding grounds are believed to be in Northeast Asia, primarily the Russian Far East, as well as the mountainous regions bordering Northeast China and the Korean Peninsula. Their wintering areas include the coasts and islands of the Sea of Japan and the Yellow Sea. The known habitats of the Crested Shelduck are mainly mountainous and forested areas, as well as river estuaries.

The Crested Shelduck is a mysterious waterfowl, never widely distributed in modern times, with sightings being sporadic. Some hypothesize that it is a relict species that was more widespread in prehistoric times, but there is no solid fossil evidence to support this. Japanese literature and paintings from the Edo period (17th to 19th centuries) frequently mention the Crested Shelduck under the name “Korean Mandarin Duck,” possibly indicating a significant population in the Korean Peninsula during that time3. The reasons for the population’s decline to the point of probable extinction are unclear, but human hunting and habitat degradation due to agricultural development are suspected.

The last confirmed wild sighting of the Crested Shelduck was on May 16, 1964, when Russian researchers observed three individuals near the Rimsky-Korsakov Islands southwest of Vladivostok, mingling with a flock of Harlequin ducks4. In March 1971, there was a sighting of two males and four females in North Hamgyong Province, North Korea5. There were also a series of unverified sightings in Northeast China during the 1980s6.

In 1890, only one Crested Shelduck specimen was known to exist, the female specimen in Copenhagen, suggesting this illustration was based on that specimen. Additionally, the prevailing view at the time still considered the Crested Shelduck not a distinct species but a hybrid.

-

Errol Fuller, Extinct Birds, New York, Ny U.A.: Facts On File Publ, 1987, p14. ↩︎

-

LIVEZEY, B. C. (2008). A phylogenetic analysis of modern sheldgeese and shelducks (Anatidae, Tadornini). Ibis, 139(1), 51–66. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919x.1997.tb04504.x ↩︎

-

Kakizawa, Ryozo, and Hiroshi Sugawara. “Twenty Japanese Sketches of Extinct Crested Shelduck Tadorna cristata (Kuroda) from the Edo Period (1603-1867).” Journal of the Yamashina Institute for Ornithology 21.2 (1989): 326-339. ↩︎

-

Labzyuk WI (1972): Chochlataya pyeganka w yuzhnom Primorye (Crested Shelduck in the Southern Primorye). Ornitologia (Moskva) 10:356-357. Cited from: Nowak E. Die Schopfkasarka, Tadorna cristata (Kuroda 1917)-eine vom Aussterben bedrohte Tierart (Wissensstand und Vorschläge zum Schutz)[J]. Bonn. zool. Beitr, 1983, 34: 235-271. ↩︎

-

Myong Sok O. Wiederentdeckung der Schopfkasarka, Tadorna cristata, in der Koreanischen Demokratischen Volksrepublik[J]. Journal of Ornithology, 1984, 125(1): 102-103. The credibility of this sighting has been questioned. See (N. J. Collar, 2001)。 ↩︎

-

In 1983, under the initiative of Dr. Nowak Eugeniusz, Northeast Asian countries launched a search for the Crested Shelduck, but it was unsuccessful. An investigation team led by Zhao Zhengjie conducted a survey on the Crested Shelduck in Northeast China between 1985 and 1991, with many sighting records from this period, including recollections of sightings before 1985. See: Zhao Zhengjie. “The history and controversy on the study of Crested Shelduck.” China Nature, 1992(4): 3. ↩︎